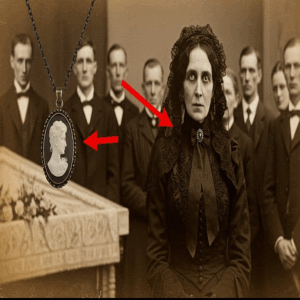

Welcome to Shadow Frames, where the past reveals its darkest secrets. Today, we delve into a story that begins with a simple photograph, an image captured in the somber atmosphere of a funeral in 1889. At first glance, nothing seems a miss, just another memorial portrait common in the Victorian era.

But, as we’ll discover, appearances can be deceiving, and sometimes the truth lies hidden in plain sight. This is the tale of a widow’s necklace and the terrible secret it concealed. The photograph was discovered in an old cedar chest tucked away in the attic of the Blackwood estate. The grand house had stood empty for decades before being purchased by the Harrington family in the autumn of 1956.

The Blackwood mansion was an imposing structure of red brick and white limestone trim with tall, narrow windows and ornate gables typical of the Victorian Gothic Revival style. It stood at the end of a long winding drive lined with ancient oak trees, their gnarled branches reaching toward the sky like arthritic fingers.

Local children had long whispered that the house was haunted, though few could articulate exactly why they felt such unease when passing its row iron gates. Martha Harrington, with her keen eye for antiques and passion for history, had fallen in love with the house despite its reputation and dilapidated condition.

A woman of 45 with prematurely silver hair and bright inquisitive eyes, Martha had convinced her husband Henry that the house could be restored to its former glory. Henry, a successful attorney who indulged his wife’s passion for historical preservation, had agreed somewhat reluctantly.

The purchase price had been surprisingly reasonable given the size and craftsmanship of the estate, but the cost of restoration had quickly mounted. It was during the renovation of the attic, a vast space with exposed beams and dormer windows that offered views of the surrounding countryside, that Martha discovered the cedar chest. It sat in a corner, partially hidden beneath old draperies and a tarp covered in decades of dust.

The chest itself was beautifully crafted with intricate carvings of roses and ivy along its sides and lid. A tarnished brass lock secured the contents, but the key was still in place, as if the last person to access the chest had intended to return. Martha was delighted to find the chest filled with momentos from a bygone era, yellowed letters tied with faded ribbons, calling cards, dance programs with tiny attached pencils, pressed flowers, small books of poetry with handwritten inscriptions, and leatherbound photo albums. The scent of

lavender and old paper filled the air as she carefully examined each item. Her historian’s mind already cataloging and contextualizing these artifacts of Victorian life. Most of the photographs were typical family portraits. Stiff, formal poses of stern-faced men and women dressed in the height of Victorian fashion.

Men in frock coats and high collars. Women in bustled dresses with tight fitting bodesses. children standing unnaturally still, their eyes fixed on some point beyond the camera. These were not casual snapshots, but carefully composed tableau meant to project respectability and social standing. But one photograph stood apart from the rest.

It showed a funeral scene, a man laid out in a coffin surrounded by mourners dressed in black. Death photography or momento mori had been common in the Victorian era when mortality rates were high and photographs were expensive luxuries. For many families, a death portrait might be the only image they possessed of a loved one.

The Victorians had a complex relationship with death, surrounding it with elaborate rituals and expressions of mourning that might seem morbid to modern sensibilities, but reflected their deep engagement with mortality as an inevitable part of life. James Blackwood read the inscription on the back of the photograph written in elegant copper plate handwriting, “Departed this earthly realm on September 18th, 1889.

May he find in heaven the peace that eluded him in life.” This last phrase struck Martha as odd, a subtle suggestion that James Blackwood’s life had been troubled in some way. Martha studied the image with a historian’s interest. The photograph was remarkably well preserved, allowing her to make out the details with clarity.

James Blackwood appeared peaceful in death, his hands folded over his chest, a slight smile frozen on his lips, the mortician’s art giving him the appearance of one merely sleeping. He was dressed in his finest suit, a gold watch chain visible across his waist coat, his hair neatly combed. Surrounding the coffin were several figures, their faces solemn and drawn with grief or what appeared to be grief.

Martha recognized the performative aspect of Victorian mourning, the expected public display of sorrow regardless of one’s private feelings. At the head of the coffin stood a woman dressed in elaborate morning attire, a black silk dress with jet beating that caught the light, a heavy veil of black crepe partially covering her face, and around her neck a necklace that caught Martha’s eye.

It was a cameo pendant, oval in shape, hanging from a black ribbon, even in the sepia tones of the photograph. The pendant seemed to draw the eye, its lighter color standing out against the woman’s dark dress. Martha thought little of it at first. Victorian morning jewelry was common, often containing a lock of the deceased’s hair or made from materials like jet or onyx.

Women in mourning were expected to adhere to strict rules regarding their appearance, with specific stages of mourning requiring different attire and accessories. During the first year of deep mourning, only the most somber jewelry was permitted. Certainly nothing that might be considered decorative or frivolous.

But as she examined the rest of the contents of the chest, she began to piece together the story of the Blackwood family through letters, diaries, and newspaper clippings, what emerged was a tale far darker than she could have imagined, a web of secrets and lies that had remained hidden for nearly 70 years. Elizabeth and James Blackwood had been prominent figures in society.

James was a successful businessman who had made his fortune in textiles, establishing mills throughout New England that employed hundreds of workers. His business practices were ruthless but effective, allowing him to amass considerable wealth by the time he was 40. Elizabeth, 10 years his junior, was known for her beauty, charm, and impeccable taste.

With chestnut hair, striking green eyes, and a slender figure, she had been considered one of the most beautiful women in the county. They had married in 1885, and to all outward appearances, theirs was a match made in heaven. the handsome, successful businessman and his lovely, accomplished wife, presiding over a mansion filled with every luxury the late 19th century could provide.

But the letters Martha found told a different story. Correspondence between Elizabeth and her sister Caroline revealed a marriage fraught with tension and unhappiness. James was described as controlling, quick to anger, and possessive. Elizabeth wrote of her growing despair, of feeling trapped in a gilded cage, her every movement monitored, her friendship scrutinized, her independence gradually eroded by a husband whose charm in public masked a very different demeanor in private. “He watches my every move,” she wrote in one letter dated March 1889. The paper, now yellowed with age,

but the ink still clearly legible and flies into a rage should I speak to another gentleman for too long. Last night after the Pemrooks dinner party, he accused me of improper behavior with Mr. Lawrence. I tried to explain that we were merely discussing the latest novel by Mrs. Ward, but he would not listen. He called me terrible names, Caroline.

Words I cannot bring myself to repeat, even to you. I fear his jealousy grows worse with each passing day. The bruises on my wrist from where he gripped me have faded, but the memory of his rage has not. I find myself constantly afraid walking on eggshells lest I provoke another outburst.

In another letter dated June of the same year, Elizabeth wrote, “Caroline, I confess I sometimes entertain dark thoughts. What freedom would be mine if James were no longer here? But then I remember my vows before God and banish such wickedness from my mind. Still, I cannot help but wonder if there might be some escape from this misery.

I have considered leaving, fleeing to you in Boston, but he has made it clear he would find me wherever I went. And what then? I have no money of my own. He keeps me on a strict allowance and reviews every expenditure. I cannot work, having no skills that might earn a living, and the scandal of separation would ruin us both socially.

I am trapped, dear sister, as surely as any prisoner in a cell, though my prison has silk wallpaper and servants to attend my every need. The correspondence abruptly stopped in early September, resuming only after James’s death. The cause of death, according to a newspaper clipping dated September 20th, 1889, was heart failure.

Sudden but not entirely unexpected given his family’s history of heart ailments. James’s father had died at 45 from a similar condition, and his older brother had experienced episodes of chest pain and shortness of breath for years. The article mentioned that James had been in good spirits the evening before his death, having hosted a small dinner party for close friends and business associates.

Among the guests listed was a Mr. Alexander Lawrence, described as a gentleman of culture and refinement recently returned from extended travel abroad. The name caught Martha’s attention, recalling Elizabeth’s letter about James’s accusation of improper behavior with this same Mr. Lawrence.

According to the article, James had retired to bed around 11:00, appearing in good health. His valet had found him unresponsive the following morning when bringing his breakfast tray. The doctor had been summoned immediately, but could only confirm that death had occurred sometime during the night.

Given James’ family history and the absence of any suspicious circumstances, no further investigation had been deemed necessary. Martha’s curiosity grew as she read Elizabeth’s letters following her husband’s death. There was grief expressed in her words, but also a sense of relief that seemed inappropriate for a newly bererieved widow.

The Victorian era demanded elaborate displays of mourning, particularly from widows who were expected to observe a full 2 years of mourning, with the first year being one of deep mourning, characterized by heavy black clothing, minimal social engagement, and a focus on the memory of the deceased. Elizabeth’s letters suggested she was observing these customs in public while privately experiencing emotions quite at odds with the expected grief. “I am learning to breathe again,” Elizabeth wrote to Caroline in October 1889.

“The house no longer feels like a prison. I maintain all the proprieties, of course. I am seen only in the deepest black. I have declined all social invitations, and I speak of James only in terms of the greatest respect. But I cannot pretend with you, dear sister. For the first time in years, I am free.

Free from his rages, from his suspicions, from the constant fear that shadowed my days. Is it wicked to feel such relief? If so, then I must confess my wickedness, for I cannot summon the grief that society demands of me. More intriguing still was a letter dated November 1889, in which Elizabeth mentioned a gift from a Mr.

Alexander Lawrence, the same gentleman James had accused her of improper behavior with months earlier, and who had been present at the dinner party the night before James’s death. “Alexander has presented me with a most exquisite cameo pendant,” she wrote. “It is carved from shell with a profile that, though not explicitly his own, bears a remarkable resemblance to him.

It is not appropriate for me to accept such a gift during my morning period, of course, but I have kept it hidden away. Perhaps when sufficient time has passed, I might wear it in remembrance not of what was, but of what might be. He has been most attentive in his visits, always observing the strictest propriety in the presence of others.

But when we are alone, there passes between us a current of understanding that needs no words. He knew Caroline. He knew what my life with James was truly like, and he offered friendship when I most needed it. Whether that friendship might blossom into something more, only time will tell.

For now, it is enough to know that I am not alone in my secret relief at James’s passing. Martha returned to the funeral photograph with new interest, examining the cameo pendant around Elizabeth’s neck more carefully. Something about it seemed odd, out of place for a widow in deep mourning. Victorian etiquette dictated that morning jewelry should be somber, made of jet or containing a momento of the deceased, such as a lock of hair preserved under glass or woven into intricate patterns.

The cameo, with its carved profile, seemed too decorative, too personal for such an occasion, especially given the strict rules governing a widow’s appearance during the first months after her husband’s death. Using a magnifying glass, Martha studied the image more closely.

The cameo appeared to be carved with a profile, but not as was traditional of a classical figure or of the deceased. Instead, it seemed to be the profile of a man with distinct features. A strong jaw, a straight nose, and wavy hair swept back from his forehead. It was difficult to make out precise details in the sepia toned photograph, but the profile appeared to be that of a man in his prime, not the idealized figures from mythology or ancient history that typically adorned cameos.

Among the collection of photographs in the chest, Martha found a portrait of Alexander Lawrence. The photograph showed a handsome man in his early 30s with an aristocratic bearing and thoughtful expression. His features were distinctive, the strong jawline and Roman nose that Elizabeth had alluded to in her letters, the wavy hair that fell across his brow in an artfully casual manner.

Comparing the tiny carved profile on the cameo with the photograph, she was struck by the resemblance. Elizabeth appeared to be wearing a pendant bearing the likeness of her rumored lover at her husband’s funeral. The impropriy of such an action would have been scandalous in Victorian society. For a widow to display, however discreetly, a token of affection from another man, especially at her husband’s funeral, would have been seen as not merely tasteless, but morally reprehensible.

Had anyone at the funeral recognized the significance of the pendant? Had Elizabeth worn it as a private act of defiance, a secret symbol of the freedom she now anticipated, visible to all, yet understood by none, save herself and perhaps Alexander. But was it merely a breach of etiquette? Or did it hint at something darker? Martha’s suspicions deepened as she discovered a small diary hidden in a secret compartment of the chest.

The compartment was revealed only when she noticed a slight discrepancy in the measurements of the chest’s interior compared to its exterior dimensions. A gentle pressure applied to a particular rose in the carved decoration released a small spring mechanism exposing a narrow space behind the chest’s inner panel.

The diary was bound in soft blue leather, its pages edged in gold with EB embossed on the cover in elegant script. It belonged to Elizabeth, and the entries spanning the months before James’s death revealed a woman desperate for escape. She wrote of meetings with Alexander, of stolen moments of happiness, and of growing resolve. April 12th, 1889. One entry read, “Met a in the park today, as if by chance. Mrs.

Pembroke was with me as chaperon, but she is nearly deaf and was content to sit on a bench while A and I walked ahead, maintaining a proper distance, but able to speak without being overheard. He understands my situation better than anyone. His own marriage, though ended by the death of his wife, rather than the cruelty I endure, was similarly unhappy. He spoke today of freedom, of the possibility of a different life.

I dare not hope too much, but his words have kindled a flame within me that I thought had been extinguished long ago. Another entry dated July 23rd, 1889. Jay struck me again today. This time across the face, hard enough to leave a mark that even powder cannot fully conceal. The pretext was trivial, a button missing from his shirt.

But the real cause was his discovery of a book of poetry A had lent me. Jay found it in my desk drawer and flew into one of his rages, accusing me of all manner of impropriy. I maintained that the book was lent to me by Mrs. Pembroke, and he seemed to accept this explanation eventually, but the damage was done. I cannot continue to live this way.

I have written to Caroline asking if she might receive me in Boston, but I know Jay would never allow me to leave. He has made it clear that he would rather see me dead than free of him. an entry dated August 10th, 1889. A has given me the most extraordinary gift, a cameo pendant carved with his profile.

It is exquisitly done, the work of an Italian artisan he commissioned during his travels last year. He had intended it for his sister, he says, but feels it should be mine. I cannot wear it openly, of course, but I keep it hidden in my jewelry box beneath the false bottom where Jay will never find it.

When I hold it, I feel a connection to a a promise of something I dare not name even in these private pages. And then most disturbingly, an entry dated September 15th, 1889, just 3 days before James’s death, chilled Martha to the bone. It is decided there can be no turning back now. A has procured what we need and assures me it will appear as natural.

Jay’s heart, already weak from his family condition, will simply stop. No one will question it. And then after a suitable period of mourning, we might find our way to each other without scandal. I tremble not with fear, but with anticipation of freedom. The diary ended there with no further entries. Martha sat back, the implications of what she had discovered sinking in.

The photograph that had first caught her attention now seemed ominous. A documentation of not just a funeral, but potentially of a murder. And there in plain sight, Elizabeth Blackwood wore the evidence around her neck, a token from the man who had helped her escape her marriage in the most permanent way possible.

The next day, Martha visited the local historical society, curious to learn more about the fate of Elizabeth Blackwood and Alexander Lawrence. The historical society was housed in a former bank building on the town’s main street. Its granite facade and columns giving it an air of somnity appropriate to its function as guardian of the town’s past.

Inside the high-sealing main room was lined with glass cases containing artifacts from the town’s history. Native American arrowheads, colonial era documents, Civil War uniforms and weapons, and photographs documenting the town’s growth and development. Martha was greeted by the society’s curator, Dr.

Harold Jenkins, a retired history professor with a well-trimmed white beard and gold- rimmed spectacles. When she mentioned the Blackwood family, his eyes lit up with interest. The Blackwoods, yes, one of our most prominent families in the late 19th century. Quite a tragic history, as I recall. We have quite a collection of materials related to them in our archives.

May I ask what your interest is? Martha explained that she and her husband had purchased the Blackwood estate and that she had discovered some family artifacts in the attic. She didn’t mention the diary or her suspicions about James’s death, simply expressing a general interest in the family’s history. Dr.

Jenkins led her to a back room where the archives were stored in metal cabinets and acid-free boxes carefully organized and labeled. He pulled several folders containing newspaper clippings, public records, and photographs related to the Blackwood family. What Martha discovered completed the tragic tale. According to local records, Elizabeth had indeed emerged from her morning period, and after a respectable interval, had become engaged to Alexander Lawrence.

Their engagement was announced in the spring of 1891, approximately 18 months after James’ death. The announcement in the local newspaper described Elizabeth as the widow of the late James Blackwood, a respected businessman and pillar of our community and Alexander as a gentleman of independent means known for his patronage of the arts and his extensive travels.

The wedding was planned for August of that year, but it never took place. In July of 1891, Elizabeth had been found dead in her bedroom, an empty bottle of Ldinum by her side and a note clutched in her hand. Linum, a tincture of opium readily available in the Victorian era, was commonly used for pain relief, insomnia, and anxiety, but was also a frequent means of suicide due to its potency and availability.

The coroner’s report listed the cause of death as self-administration of a lethal dose of ldinum with evident intent to end life, a clinical description of what was, in plain terms, suicide. The contents of the note were not recorded in the public documents, but rumors had swirled that it contained a confession.

Dr. Jenkins showed Martha a diary entry from Mrs. Elellanar Pembroke, the same woman mentioned in Elizabeth’s letters as her chaperon and friend. Mrs. Pembroke wrote, “The town is a buzz with talk of Mrs. Blackwood’s tragic end. It is whispered that she left a letter confessing to some terrible deed, though the exact nature of this confession is known only to those who found her.” Mr.

Richard Blackwood, who arrived to settle his sister-in-law’s affairs, has refused all comment, saying only that Mrs. Blackwood’s mind had been unbalanced by grief. The wedding, of course, will not take place, and Mr. Lawrence has secluded himself at his country home, overcome with sorrow. Alexander Lawrence had left town shortly thereafter, his reputation in tatters.

He was never formally accused of any crime, but suspicion followed him. He died in obscurity some years later, never having married. The Blackwood estate had passed to James’ younger brother, Richard, who had maintained it for some years before his own death in 1897. Richard had never married, and with no direct heirs, the property had changed hands several times before finally being purchased by the Harringtons. One additional detail caught Martha’s attention.

A small notice in the newspaper dated August 3rd, 1891, just days after Elizabeth’s suicide, announcing the sale of her personal effects. The belongings of the late Mrs. Elizabeth Blackwood will be sold at auction on August 10th at the Blackwood estate. The notice read. Items include furnishings, books, artwork, and personal accessories. Proceeds will benefit the town orphanage as directed by Mr. Richard Blackwood.

Martha wondered if the cameo pendant had been among the items sold, and if so, whether the buyer had any idea of its significance, or had Richard Blackwood discovered its importance and disposed of it privately to protect the family name. The trail seemed to end there, with no way to know what had become of this crucial piece of evidence.

Martha debated what to do with her discovery. The events had occurred nearly 70 years ago, with all the principles long dead. Did it matter anymore if James Blackwood had been murdered? Would exposing the truth serve any purpose other than to tarnish the reputations of people who could no longer defend themselves? In the end, she decided to document her findings, but kept them private, sharing them only with her husband.

Henry Harrington, a practical man with a lawyer’s appreciation for evidence, was skeptical of Martha’s interpretation. “It’s a compelling story, my dear,” he said after listening to her account. “But you’re making quite a leap from these letters and diary entries to a conclusion of murder.” The diary entry about what we need could refer to anything. Perhaps they plan to elope.

And the reference to James’ heart was merely the expectation that the shock of his wife’s desertion might aggravate his existing condition. And wearing the cameo at the funeral, while certainly in poor taste, is hardly proof of criminal intent.

Martha conceded that her evidence was circumstantial, but she remained convinced that something sinister had occurred at the Blackwood estate in September 1889. She carefully returned the photograph, letters, and diary to the cedar chest and placed it back in the attic. The chest remained there until Martha’s death in 1982 when her son, Thomas Harrington, discovered it while sorting through his mother’s possessions.

Thomas, less sensitive to the moral implications of the tale than his mother had been, saw the potential for notoriety. He had the photograph restored and enlarged, making the details of the cameo pendant clearer. He began to share the story with friends and local historians, and soon the tale of Elizabeth Blackwood and her telltale necklace became something of a local legend. But legends have a way of growing and changing with each telling.

And as the story spread, new details emerged, some factual, others embellished or entirely fabricated. The story became a fixture of local ghost tours and historical walking tours with guides pointing out the Blackwood estate, now the Harrington House, and recounting increasingly dramatic versions of Elizabeth and Alexander’s alleged crime.

One persistent rumor suggested that Elizabeth had not taken her own life, but had been murdered by James’ brother, Richard, who had discovered her role in James’ death. According to this version, Richard had confronted Elizabeth with evidence of her crime, possibly the cameo pendant itself, and had forced her to write a suicide note confessing to the murder before administering the ldinum himself. His motive supposedly was twofold.

To avenge his brother and to gain control of the Blackwood fortune. Another rumor claimed that Alexander Lawrence had been blackmailing Elizabeth, threatening to expose her unless she shared James’ fortune with him. In this telling, Elizabeth’s suicide was an act of desperation when she could no longer meet his demands.

This version portrayed Alexander not as a devoted lover who had helped Elizabeth escape an abusive marriage, but as a calculating opportunist who had manipulated a vulnerable woman for financial gain. Still, another suggested that the cameo pendant contained not just Alexander’s likeness, but a compartment that had held the poison used to kill James.

Such lockets containing hidden compartments for poison, locks of hair, or tiny portraits were not unknown in the Victorian era, adding a layer of plausibility to this embellishment. The truth, as is often the case, was likely somewhere in between these elaborate tales.

What remains undisputed is the existence of the photograph with its seemingly peaceful funeral scene and the widow’s damning necklace. In 1998, the photograph was donated to the county museum where it was included in an exhibition on Victorian morning customs. The museum, a modern building of glass and steel that contrasted sharply with the historical artifacts it housed, dedicated a small corner of the exhibition to the Blackwood story.

The photograph was displayed alongside a brief text that outlined the known facts while acknowledging the speculations that had grown around it. Few visitors paid it much attention, seeing only another example of the Victorian’s complex relationship with death and remembrance. But for those who knew the story, who looked closely at the widow’s necklace and understood what it represented, the photograph remained a chilling reminder that appearances can be deceiving, and that sometimes the most damning evidence is hidden in plain sight. The photograph now hangs in a quiet corner of the museum, the truth it contains known to only a few. But if you

look closely, if you zoom in on the widow’s necklace, you might just glimpse a secret over a century old. A secret that transformed a simple funeral portrait into a record of betrayal, murder, and ultimate justice. As for the Blackwood estate, it still stands on the outskirts of town, having passed through many hands since the Harringtons.

The current owners have renovated it extensively, stripping away the dark Victorian wallpaper and heavy draperies, replacing them with light, bright colors and modern furnishings. The house no longer feels oppressive, visitors say, though some claim to feel a chill in certain rooms, particularly the master bedroom where James Blackwood died and the smaller bedroom where Elizabeth allegedly took her own life.

Current residents report no unusual occurrences, no ghostly manifestations of James or Elizabeth. The house keeps its secrets as it has for generations. The cedar chest that contained the evidence of Elizabeth’s crime was lost in a fire that destroyed part of the Harrington house in 1990.

Though copies of the photograph and transcriptions of the letters and diary had been made beforehand. But sometimes on quiet September evenings when the light fades and shadows lengthen, visitors to the old cemetery where James and Elizabeth Blackwood lie buried report a strange phenomenon. A figure dressed in the black garb of a Victorian widow can be seen moving between the gravestones, one hand clutching at her throat as if trying to hide or perhaps display something hanging there.

The figure never approaches visitors, maintaining a distance that makes details difficult to discern, but those who have glimpsed her describe a sense of profound sadness and regret emanating from the apparition. Whether this is merely a trick of the light or something more supernatural remains a matter of speculation, but those who know the story of the funeral photograph and the widow’s necklace cannot help but wonder if Elizabeth Blackwood’s spirit remains bound to this earth, unable to escape the consequences of her actions even in death.

And now, as the photograph lies before us, we too become part of this story. Witnesses to a crime committed long ago, preserved forever in the sepia tones of a funeral portrait that looks peaceful until you zoom in on the widow’s necklace. But our story doesn’t end with Elizabeth’s apparent suicide.

The truth, as is often the case, runs deeper and darker than initial appearances suggest. In 2002, Thomas Harrington’s daughter, Amelia, inherited the collection of Blackwood family documents that had survived the fire.

A slender woman in her 40s with her grandmother’s silver streak dark hair and keen eyes, Amelia had pursued a career in historical preservation, working as a curator for several prestigious museums before returning to her hometown to establish a historical research center. Unlike her father, who had been content to share the Blackwood story as a sensational tale, Amelia was a meticulous researcher with a background in archival sciences.

She approached the Blackwood mystery with scholarly precision, seeking to separate fact from the fiction that had accumulated around the story over the decades. Her investigation led her to documents that had not been part of the original collection found in the cedar chest.

Through careful research in various archives and private collections across New England, she pieced together a more complete picture of the events surrounding James Blackwood’s death and the aftermath. The local historical society had expanded significantly since Martha’s initial visit in the 1950s, now occupying a restored Victorian mansion that had once belonged to the Pemroke family, the same Pembrooks mentioned in Elizabeth’s letters.

The society’s archives had grown as well, incorporating private collections donated by longtime residents and materials from regional libraries and museums. One of Amelia’s most significant discoveries was a series of letters exchanged between Alexander Lawrence and his cousin, Dr. Henry Lawrence, a physician practicing in a neighboring town.

These letters, preserved in the Lawrence family archives and previously overlooked by researchers, focused on the more obvious Blackwood connections, cast the events in a new and even more disturbing light. In a letter dated August 1889, Alexander wrote to his cousin, “I find myself in a most troubling situation. Mrs.

B speaks increasingly of permanent solutions to her unhappiness. I have counseledled patience and discretion, but she grows more desperate with each passing day. Her husband’s treatment of her is indeed abominable. Yet I fear she may take actions that will lead to ruin for us both.

She has inquired about certain substances and their effects on the heart. I have of course expressed horror at such suggestions, but I worry she will seek assistance elsewhere if I do not appear sympathetic to her plight. What would you advise, cousin? I cannot bear to think of her continuing to suffer. Yet I cannot condone the course she seems determined to pursue. Dr.

Henry’s reply was cautious but revealing. I understand the delicacy of your position, cousin. The lady’s situation sounds intolerable, and her distress is natural. However, I must caution you in the strongest possible terms against involving yourself in any scheme that might be construed as criminal.

The substances she inquires about would indeed produce the effect she desires and would be difficult to detect unless specifically sought out, which is precisely why you must distance yourself from such discussions. Her husband’s heart condition would make any investigation prefuncter at best. But should suspicion arise, association with such a plot would mean destruction for a man in your position.

Urge her to seek legal counsel regarding separation, though I understand the obstacles to such a course. Perhaps a temporary residence with relatives might provide respit while a more permanent solution is sought. Above all, protect yourself from entanglement in desperate actions that might be contemplated in the heat of emotion, but regretted bitterly in cooler moments.

The correspondence continued with Alexander expressing growing concern about Elizabeth’s state of mind and determination. His letters described a woman increasingly fixated on the idea of permanent escape from her marriage, alternating between periods of resignation and moments of frantic planning. Alexander’s own feelings were clearly complex. Deep affection for Elizabeth mingled with fear for her well-being and concern about the moral and legal implications of the course she seemed determined to pursue.

In early September, just days before James’s death, Alexander wrote in apparent distress, “It may already be too late.” When last we met, she spoke as if the deed were already accomplished, though I know this cannot be the case, as her husband still lives. She showed me a small vial and said, “This is my freedom.

” I tried to dissuade her to make her understand the gravity of what she contemplated, but she merely smiled and said, “It is already done. I know not what she meant, but I fear the worst. Should anything happen to JB, I will be implicated by my knowledge and failure to alert the authorities. Yet, how can I do so without exposing her and destroying us both? I find myself trapped in a web of her making, unable to extricate myself without causing the very harm I seek to prevent. Dr. Henry’s reply never reached Alexander.

According to postal records Amelia uncovered, it was delivered to the Lawrence residence on September 19th, 1889, the day after James Blackwood’s death, when Alexander was likely already aware that his warnings had come too late. These letters suggested that while Alexander may have been aware of Elizabeth’s intentions, he had not actively participated in the murder and had in fact attempted to dissuade her.

This contradicted the long-held belief that they had conspired together to eliminate James. Instead, it painted a picture of a man torn between his feelings for a woman in a desperate situation and his own moral compass, ultimately unable to prevent a tragedy he had seen coming.

But the most startling discovery came from medical records and a private journal kept by Dr. William Porter, the physician who had attended to both James Blackwood’s death and Elizabeth’s suicide nearly 2 years later. Dr. Porter had been a prominent physician in the community, serving the town’s elite families for over 40 years.

His detailed records and personal observations, donated to the medical school, where he had later taught, provided a perspective that had been missing from the public accounts. Dr. Porter had been called to the Blackwood residence on the morning of September 18th, 1889 after a maid found James unresponsive in his bed. His initial examination led him to pronounce death by heart failure, consistent with the known family history of heart disease, but privately he had harbored doubts.

In his journal, he wrote, “Blackwood’s death presents certain inconsistencies. While the symptoms are generally consistent with heart failure, the dilation of the pupils and slight discoloration of the fingernails give me pause. These might suggest ingestion of certain substances, though they could also be explained by the natural processes following death without specific cause for suspicion. I cannot justify the expense and potential scandal of a more thorough examination.

The family’s reputation in the community and Blackwood’s known heart troubles make a natural death the most plausible explanation. Mrs. Blackwood appears appropriately distressed, though there is something in her manner that strikes me as performative rather than genuine. Perhaps I am being uncharitable.

Grief manifests in many ways, and she would not be the first widow to feel relief mingled with sorrow at the passing of a difficult husband. Yet, I cannot shake the feeling that all is not as it appears. More telling still were Dr. Porter’s notes from July 1891, when he was called to attend to Elizabeth. Mrs.

Blackwood’s suicide leaves little doubt as to her intentions. The empty Ldinum bottle and note beside her make the cause clear. What troubles me is the content of the note, which I was able to read before Mr. Richard Blackwood, James’ brother, took possession of it.

In it, she confessed to having poisoned her husband nearly 2 years ago, describing in detail how she had administered small doses of arsenic over several weeks, culminating in a final fatal dose the night of his death. The gradual introduction of the poison, she wrote, had produced symptoms easily mistaken for a worsening heart condition, while the final dose ensured his death appeared to be the natural culmination of this decline.

She wrote of remorse, not for the act itself, but for having implicated Mr. Lawrence, who she claimed had no knowledge of her actions, despite her attempts to suggest otherwise to ensure her own protection should suspicions arise. She described how she had deliberately created the impression of his involvement, going so far as to wear a cameo bearing his likeness at her husband’s funeral, a detail I had not noticed at the time, but which now seems a calculated risk, a declaration of her true allegiance, visible to all, yet understood by none. She wrote of being haunted by her

husband’s spirit and unable to bear the guilt any longer. Most disturbing was her description of wearing a cameo pendant bearing Lawrence’s likeness at her husband’s funeral, calling it both her greatest triumph and most terrible mistake.

She believed that someone had noticed this impropriy and had been blackmailing her these past months, though she did not name this person. The note ended with a plea for forgiveness, not from God or society, but from Lawrence himself, whom she felt she had betrayed by drawing him into her scheme against his will and better judgment. This journal entry upended the narrative that had developed around the photograph.

Elizabeth had acted alone in murdering her husband, deliberately creating the impression that Alexander was her accomplice as a form of insurance. The cameo pendant had indeed been a clue, but not one that Elizabeth had intended to leave. Her wearing of it at the funeral had been an act of defiance, a private celebration of her newfound freedom and the future she anticipated with Alexander, not realizing that this very token would eventually lead to her downfall, but who had noticed the pendant and deduced its significance, who had been blackmailing Elizabeth in the months leading up to

her suicide. Amelia’s research led her to correspondence between Richard Blackwood, James’s brother, and various associates in the months following James’s death. Richard had been excluded from his brother’s will with the bulk of the estate passing directly to Elizabeth. He had contested the will but had been unsuccessful.

The courts had upheld James’ wishes, leaving Richard with only a small annual allowance that he considered insulting given his position as the last male Blackwood. In a letter to his solicitor dated March 1891, Richard wrote, “I am increasingly convinced that Jay’s death was not natural. The widow’s behavior since her bereiement has been most inappropriate.

She maintains the outward appearance of mourning, yet I have information suggesting clandestine meetings with L. I have also come into possession of certain evidence that might shed light on the circumstances of my brother’s passing.

Should this evidence be brought to the attention of the authorities, I believe a very different conclusion might be reached regarding both the cause of his death and the rightful disposition of his estate. The evidence Richard referred to was not explicitly identified, but subsequent events suggested it was knowledge of the significance of the pendant in the funeral photograph.

Richard, who had been present at the funeral, may have recognized Alexander Lawrence’s likeness in the cameo, and understood the implications of Elizabeth wearing such a token at her husband’s funeral. Financial records showed that in the months before her death, Elizabeth had made several substantial withdrawals from her accounts.

No corresponding expenditures could be traced, suggesting that these funds might have been used for blackmail payments. The pattern of withdrawals increased in frequency and amount as the date of her engagement announcement approached, indicating escalating demands from her blackmailer. The final piece of the puzzle came from the report of the constable who had investigated Elizabeth’s suicide.

Tucked away in the official file was a statement from Elizabeth’s lady’s maid, who reported that in the weeks before her death, Elizabeth had received several unmarked envelopes that had caused her great distress. After reading the contents, Elizabeth had burned the letters in the fireplace, but the maid had glimpsed what appeared to be a small photographic print enclosed with one of them, likely a detail from the funeral photograph focusing on the pendant.

The maid also reported that on the night before her death, Elizabeth had received a visitor, a man who had stayed for only a short time, but whose departure had left Elizabeth in a state of agitation. She had gone directly to her writing desk afterward, and had remained there until late in the night.

The visitor had not given his name to the servants, but the maid’s description matched Richard Blackwood. Amelia’s research suggested a new narrative. Elizabeth had indeed poisoned her husband, acting alone, but creating the impression that Alexander was involved to protect herself. She had unwittingly revealed her connection to Alexander by wearing his likeness in the cameo pendant at the funeral.

Richard, desperate to regain what he saw as his rightful inheritance, had noticed this detail and had used it to blackmail Elizabeth. When she could no longer meet his demands, he had threatened to expose her crime publicly. Faced with the prospect of scandal, ruin, and possibly execution, Elizabeth had chosen to end her life, but not before leaving a confession that implicated Richard in her final despair.

What had become of Richard Blackwood after Elizabeth’s death? According to public records, he had indeed inherited the estate following Elizabeth’s suicide, as she had no children, and had not changed her will to exclude him. He had lived in the Blackwood house for several years, apparently prospering, but had died in mysterious circumstances in 1897.

Found at the bottom of the Grand Staircase with a broken neck, reportedly after a fall while intoxicated, there were no witnesses to Richard’s death, and given his reputation as a moderate drinker, the circumstances raised questions that were never fully addressed.

Some in the town whispered that Justice had finally caught up with him, that Elizabeth’s ghost had pushed him down the stairs in revenge for driving her to suicide. Others suggested a more earthly explanation, that Alexander Lawrence had returned secretly to avenge Elizabeth, though there was no evidence to support this theory.

The house had passed to distant relatives after Richard’s death, none of whom had chosen to live in it, leading to its eventual sale outside the family. The Blackwood name faded from prominence, remembered primarily through the stories that continued to circulate about Elizabeth James and the cursed estate where tragedy had played out over the span of nearly a decade.

Amelia’s research brought new depth to the story of the funeral photograph, transforming it from a simple tale of murderous conspiracy to a complex web of solitary crime, manipulation, blackmail, and retribution. The pendant that Elizabeth had worn so unwisely had indeed been the key to her undoing, but not in the way the legend had suggested.

The story of Elizabeth Blackwood and the funeral photograph continued to evolve as Amelia shared her findings with historians and museum curators. The photograph itself took on new significance. No longer just a curiosity, but a vital piece of historical evidence that had helped unravel a century old mystery.

In 2010, the museum where the photograph was displayed created a special exhibition around it featuring Amelia’s research and the broader context of Victorian crime, punishment, and morning customs. The exhibition, titled Hidden in Plain Sight: The Blackwood Mystery, drew unexpected attention from both local residents and visitors from across the country who were intrigued by the story of Elizabeth and her telltale necklace.

The centerpiece of the exhibition was an enlarged version of the funeral photograph with the cameo pendant highlighted and a magnifying glass available for visitors to examine the detail. Alongside it were displayed copies of the letters, diary entries, and other documents that had been pieced together to tell the story, as well as artifacts from the Victorian era that provided context. Morning jewelry similar to what would have been considered appropriate for a widow.

Examples of arsenic packaging from the period. the poison having been readily available in various household products and items illustrating the strict social codes that had constrained Elizabeth’s options. A section of the exhibition was devoted to the evolution of the story itself, showing how the tale had changed over time.

From Martha’s initial discovery through Thomas’s sensationalized version to Amelia’s scholarly reconstruction, this meta narrative about the nature of historical investigation and the way stories transform over time became an unexpected focus of interest for many visitors.

But even as the historical record became clearer, the legends surrounding the Blackwood case continued to grow. The reported sightings of a ghostly widow in the cemetery persisted, joined now by accounts of a male figure seen falling repeatedly down an invisible staircase near the site of the old Blackwood estate, which had been demolished in the 1960s to make way for modern development.

A housing development now stood where the mansion had once dominated the landscape. Its grand architecture and troubled history preserved only in photographs and memories. But residents of the homes built on the property reported strange occurrences, unexplained sounds, objects moving without apparent cause, sudden cold spots, and fleeting glimpses of figures that vanished when directly approached.

Several families had moved out after only a few months, citing these disturbances as their reason for leaving. Whether these apparitions were genuine manifestations of the restless dead or simply the product of imagination fueled by knowledge of the tragic history, none could say with certainty.

But the story of the funeral photograph and the widow’s necklace had become firmly embedded in local folklore, a cautionary tale passed down through generations. For modern viewers, the photograph serves as a reminder of the hidden histories that surround us, the secrets concealed within seemingly ordinary objects and images.

It invites us to look closer, to question what lies beneath the surface, and to consider how the past continues to influence the present in ways both seen and unseen. The cameo pendant itself was never found. According to the inventory of Elizabeth’s possessions made after her death, no such item was listed among her jewelry.

Had Richard taken it as further evidence of her guilt? Had Elizabeth herself destroyed it in a final attempt to erase the evidence of her crime and her ill- fated attachment to Alexander Lawrence? Or could it still exist somewhere, passed down through generations, its significance unknown to its current owner? In 2015, a cameo pendant matching the description of Elizabeth’s was offered for sale at an antique auction in Boston.

The seller, an elderly woman who had inherited it from her grandmother, knew nothing of its history except that it had been purchased at an estate sale in the late 19th century. The cameo showed a profile of a man with features remarkably similar to those in the photograph of Alexander Lawrence. The auction catalog described it as a fine example of Victorian shell cameo work.

The profile rendered with exceptional detail and artistry, mounted on a silver frame and suspended from a black ribbon replaced in recent years. Amelia attended the auction but was outbid by a private collector whose identity was not disclosed.

The pendant disappeared once again into a private collection, its connection to the Blackwood case impossible to verify conclusively, but tantalizing in its implications. Had this been the actual pendant worn by Elizabeth at her husband’s funeral? Had it somehow made its way from the Blackwood estate to an anonymous buyer and then through generations of owners who had no idea of its tragic history, the question remains unanswered.

Another mystery layered onto the already complex narrative. These questions remain unanswered, adding yet another layer of mystery to a story already rich with enigma and intrigue. The boundaries between fact and legend, history and folklore, become increasingly blurred as the story is retold and reinterpreted by each generation.

What remains constant is the power of the funeral photograph to captivate and disturb to suggest that beneath the carefully composed surface of Victorian propriety lay depths of passion, desperation, and betrayal that continue to resonate with modern viewers. As for Alexander Lawrence, Amelia’s research revealed that following Elizabeth’s suicide and the scandal that ensued, he had indeed left the area, relocating to Boston and later to Europe. He had never married and had died in Paris in 1912, leaving his modest estate to various charitable

causes. Among his personal effects, according to the executive of his will, was a locked box containing a single photograph, not of Elizabeth, as might have been expected, but of the cameo pendant itself, photographed in detail to capture the carved likeness it bore. The back of the photograph bore a simple inscription, momento mori.

This Latin phrase, commonly used in Victorian morning art, translates to, remember that you will die. In the context of Alexander’s possession of this image, it takes on a more specific and poignant meaning, a reminder not just of mortality in general, but of a particular death that had altered the course of his life, and of the role that this small carved likeness had played in a tragedy that had unfolded over many years.

A journal found among Alexander’s possessions, written in a cipher that took Amelia months to decode, revealed a man haunted by guilt and regret. Though he had not actively participated in James’ murder, he had been aware of Elizabeth’s intentions and had failed to prevent the crime.

His feelings for Elizabeth had been genuine, but they had been tainted by the knowledge of her actions and by his own complicity through inaction. In an entry dated July 28th, 1891, shortly after learning of Elizabeth’s death, he wrote, “I am undone. The news of E. His desperate act has reached me, and with it the knowledge that she implicated me in her confession, not falsely, for though my hands did not administer the poison, my silence made me an accomplice. I loved her, yet I failed her.

First in lacking the courage to dissuade her from her deadly course, and then in abandoning her to face the consequences alone. The cameo that was meant as a token of affection became instead a symbol of our mutual destruction. I shall carry this guilt to my grave.” The photograph of the funeral with its seemingly peaceful scene and its hidden clue thus becomes more than just evidence of a crime.

It becomes a symbol of the complex web of human relationships, of desires and fears, of actions and their often unforeseen consequences. It stands as testimony to the truth that what we see on the surface often conceals depths of meaning and significance that become apparent only when we look more closely, when we zoom in on the details that others might overlook. In the end, the story of the widow’s necklace is not just a tale of murder and detection.

It is a reflection on the nature of evidence, on the power of small details to reveal great truths, and on the way that the past continues to speak to us through the artifacts it leaves behind, if only we have the patience and insight to listen.

The funeral photograph, now carefully preserved and digitally archived, continues to draw visitors to the museum. They lean in close, squinting at the tiny image of the pendant around Elizabeth Blackwood’s neck, trying to make out the features of the man whose likeness she wore, even as she stood beside her murdered husband’s coffin. Most can discern only a vague outline.

The limitations of 19th century photography and the degradation of the image over time, making it difficult to see clearly. But the power of the photograph lies not in what it shows clearly, but in what it suggests. In the story that unfolds when we consider not just what is visible, but what lies hidden beneath the surface.

It reminds us that the past is never as distant as it seems. That old secrets have a way of emerging into the light. and that sometimes the most important truths are hidden in plain sight, waiting for someone to look just a little closer, to zoom in on a detail that others have overlooked, and to uncover a story that might otherwise have remained forever untold.

In 2018, the Blackwood case attracted renewed interest when a graduate student in forensic pathology researching historical cases of arsenic poisoning came across Amelia’s work and the original coroner’s reports. Using modern analytical techniques to reinterpret the described symptoms, the student concluded that the pattern of James Blackwood’s death was indeed consistent with chronic arsenic poisoning culminating in a fatal dose, exactly as Elizabeth had confessed in her suicide note. The students paper published in a respected forensic journal provided scientific validation

for what had previously been primarily historical and circumstantial evidence. It described how the symptoms reported in Dr. Porter’s notes, the gradually worsening heart condition, the discoloration of the fingernails, the dilated pupils observed after death aligned perfectly with arsenic poisoning.

The paper suggested that had modern toxicology been available in 1889, James’ true cause of death would have been readily apparent, this scientific confirmation of Elizabeth’s crime brought the case full circle, connecting the Victorian tragedy to modern forensic understanding and demonstrating how advances in science can shed new light on historical mysteries.

It also sparked discussions about domestic abuse in the Victorian era, the limited options available to women trapped in violent marriages, and the ethical complexities surrounding Elizabeth’s actions. A symposium held at a nearby university brought together historians, forensic experts, psychologists, and legal scholars to discuss the case from multiddisciplinary perspectives.

One presenter compared Elizabeth’s situation to modern cases of domestic violence, noting the parallels in patterns of control, isolation, and escalating abuse. Another examined the legal status of Victorian women, particularly in marriage, highlighting how the laws of the time effectively trapped women in abusive situations by denying them control over property, custody of children, and even their own bodies.

The ethical discussion was particularly heated with participants debating whether Elizabeth’s actions could be viewed as self-defense given the ongoing abuse she suffered or whether they constituted premeditated murder regardless of the circumstances. The historical context, the lack of divorce options, the social stigma attached to separation, the absence of legal protections against domestic violence was weighed against the deliberate calculated nature of the poisoning carried out over weeks.

No consensus was reached, but the discussion illuminated the complex interplay of personal desperation, social constraints, and moral choices that had shaped Elizabeth’s decision and its aftermath. It added yet another layer to the already multiaceted story of the funeral photograph and the widow’s necklace.

As you look at this photograph today, consider what other secrets it might still hold, what other aspects of this tragic tale remain to be discovered. For while we now know much about Elizabeth Blackwood, her unhappy marriage, her desperate act, and its eventual consequences, there are still shadows in this story, still questions that may never be fully answered.

Why did Elizabeth choose to wear the cameo at the funeral, knowing the risk it posed? Was it an act of defiance, a private celebration of her freedom, or something more complex? perhaps a subconscious desire to be caught, to have her crime exposed and face the consequences. Psychology offers various interpretations from the concept of leakage, where criminals unconsciously leave clues to their guilt, to the possibility that Elizabeth wanted to demonstrate her power over both James and Alexander by flaunting this token at the most inappropriate moment possible. And what of Alexander’s role? His letters suggest he tried to dissuade

Elizabeth from her plan. Yet he did not alert the authorities or take decisive action to prevent the crime. Was his inaction born of love, fear, moral ambivalence, or some combination of these? Did he truly understand what Elizabeth intended, or did he convince himself that she was merely engaging in dark fantasy rather than actively planning murder? These questions invite us to consider the psychological complexities of the case, the inner lives of these individuals who lived and died more than a century ago. The documentary evidence provides a

framework. But within that framework, there remains space for interpretation, for empathy, and for recognition of the human capacity for both terrible acts and profound remorse. And perhaps that is as it should be. For in the end, history is not a puzzle to be solved completely, but a tapestry of interconnected lives and events that we can never fully unravel.

We can pull at the threads, follow them where they lead, but there will always be knots and tangles, patterns that remain unclear, and stories that continue to evolve with each new perspective, each new piece of evidence, each new generation that looks upon old images with fresh eyes.

The story of Elizabeth Blackwood and her telltale necklace has evolved from a local legend to a documented historical case. From a simple tale of murder and detection to a complex exploration of Victorian society, gender roles, domestic violence, and the way we interpret the past, it has been examined through the lenses of history, forensic science, psychology, law, and cultural studies.

With each new perspective, the story grows richer, more nuanced, and more relevant to contemporary concerns. So, as we come to the end of our examination of this particular photograph, this seemingly peaceful funeral scene with its telling detail of the widow’s necklace, we invite you to carry this story with you, to remember it when you look at old photographs or family heirlooms, and to consider what secrets they might hold, what stories they might tell if only we take the time to look more closely, to zoom in on the details, and to listen to the whispers of the past that still echo in the present. For every photograph, every

object from the past contains within it not just an image or a function, but a story. And in those stories, we may find not only glimpses of those who came before us, but reflections of ourselves, our own hopes and fears, our own secrets and desires, our own capacity for both terrible acts and profound remorse.

The tale of the funeral photograph and the widow’s necklace reminds us that beneath the surface of even the most ordinary images, extraordinary stories may lie hidden. It encourages us to look more closely at the world around us, to question what we see, and to remember that the truth is often more complex, more nuanced, and more surprising than it first appears.

And so we leave Elizabeth Blackwood, James, Alexander Lawrence, and Richard to their rest. Their story told, their secrets revealed. The photograph that preserved one crucial moment in their intertwined lives continues to speak to us across the decades. A silent witness to events long past but never truly forgotten.

In the quiet corners of museums and archives, in family albums and forgotten atticss, countless other photographs wait, each with its own story to tell. Some may hold secrets as dramatic as the tale of Elizabeth’s pendant, while others may speak of simpler times, of everyday joys and sorrows, of lives lived in obscurity, but no less worthy of remembrance.

It is our privilege and our responsibility to look upon these images with both curiosity and respect, to acknowledge both the distance that separates us from the past and the common humanity that binds us to those who came before. In doing so, we ensure that their stories, their experiences, and the lessons they have to teach us are not lost to time, but remain vibrant and meaningful in the present.

As for the funeral photograph that has been the focus of our attention, it continues to exert a strange fascination on those who view it. There is something compelling about the image, about the peaceful face of James Blackwood in his coffin, about the solemn figures surrounding him, and especially about Elizabeth, the widow, whose secret was hidden in plain sight, captured forever by the photographers’s lens in the form of a small pendant hung around her neck.

We may never know what Elizabeth was thinking as she stood there, whether she felt remorse or triumph, fear or relief. We can only look at her partially veiled face and wonder at the complexity of the human heart that can contain such contradictory emotions, love and hatred, desire and resentment, hope and despair. In the end, the story of the funeral photograph and the widow’s necklace is a reminder of the power of images to capture not just how things appeared, but how they truly were.

It is a testament to the enduring human fascination with mystery and revelation, with secrets hidden and secrets exposed. And it is an invitation to look more closely at the world around us, to seek out the stories that lie beneath the surface, and to remember that sometimes the most revealing details are those that at first glance seem the least significant. So the next time you look at an old photograph, take a moment to examine it carefully.

Look at the expressions on the faces, the positions of the hands, the items of clothing or jewelry that the subjects chose to wear. Ask yourself what these details might reveal about their lives, their relationships, their hopes and fears. Zoom in on the small details that others might overlook.

For who knows what secrets you might discover, what stories you might uncover, what truths you might reveal. The past is never as silent as it seems. If only we have the patience to listen, the curiosity to question, and the insight to understand the clues it is left behind, and remember the lesson of the widow’s necklace.

Sometimes the most damning evidence, the most revealing truth is hidden in plain sight, waiting for someone to look just a little closer, to zoom in on what others have overlooked, and to see what has been there all along. This is Shadow Frames, where we bring the past into focus, one photograph at a time. Until next time, keep looking closer, for the truth is often found in the details.

News

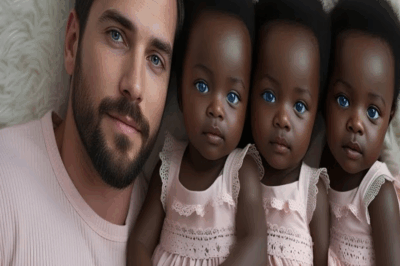

En 1995, Él Adoptó A Tres Niñas Negras — Mira Cómo Le Agradecieron 30 Años Después

En 1985, Joe Pies, joven y sin dinero, vestido con una camisa rosa pálido, entró en el tribunal de…

“Esa Es La Fórmula Incorrecta”, Susurró La Camarera Al Millonario — Justo Antes Del Acuerdo De €100M

El restaurante Michelin, la terraza real en Madrid, era el escenario perfecto para acuerdos de cientos de millones. Aquella…

Chica Pobre Encuentra Trillizos En La Basura — Sin Saber Que Son Hijos Perdidos De Un Millonario…

El llanto desgarrador de los recién nacidos resonaba en el callejón oscuro de Madrid, cuando lucía, de 7 años,…

BARONESA VIRGÍNIA RENEGADA TROCA O MARIDO PELO AMOR DE UMA MULATA – Brasil Imperial 1847

O sussurro que escapou dos lábios da baronesa Virgínia de Vasconcelos naquela manhã de junho de 1847, enquanto observava…

Cuando los obreros rompieron el altar en Chiapas, todos vomitaron al mismo tiempo

¿Alguna vez ha sentido que hay secretos ancestrales que deberían permanecer enterrados? En 1937, el ingeniero Fernando Ortiz llega…

O coronel que tirou a PRÓPRIA vida após descobrir o AMOR PROIBIDO do filho

O disparo que ecoou pela Casagrande da Fazenda Santa Adelaide na madrugada de 3 de novembro de 1843 selou…

End of content

No more pages to load