The Pond in Winter

I. There are stories that live in the marrow of your bones, stories that shape the way you move through the world. For me, one of those stories begins on a January night in 1998, when the pond behind Jed Miller’s house was breathing smoke into the bitter air and the ice was thin as a whisper.

I was a veterinarian in a small Midwestern town, the kind of place where everyone knows the names of your dogs before they know yours. My clinic sat on the edge of the county, a squat brick building with a faded sign and a waiting room that smelled faintly of kibble and antiseptic. Most nights, I’d finish my rounds early, lock up, and head home to my own quiet house. But that night, as I was stacking files and listening to the wind rattle the windows, the phone rang.

It was Jed. Vietnam vet, widower, lived on a patch of land south of town where the cattails grew taller than a man. Jed was a fixture in town—gruff but gentle, always with a word for the weather and a story about the old days. And always, always with Sam, his golden retriever. Sam was twelve, stiff in the hips, muzzle dusted with gray, but loyal as sunrise. I’d patched Sam up more times than I could count—glass cuts, porcupine quills, a run-in with a barbed wire fence. He was the kind of dog that made you feel better just by existing in the same county.

“Doc,” Jed said, voice tight, “he’s gone through the ice.”

I didn’t have to ask who he was. I grabbed my coat, tossed a rope in the truck, and drove faster than was smart on black ice.

II.

When I pulled up, the world was blue and silent. The pond was a sheet of broken glass, steam curling off the surface where the water had won out over the cold. Jed was standing at the edge, boots soaked past the ankles, breath curling sideways in the wind. He looked older than I’d ever seen him—shoulders hunched, hands red and shaking.

Sam was twenty feet out, front paws up on the jagged edge of the ice, chest in the water, trying to climb but slipping every time. His eyes found Jed and stayed there, pleading without sound.

“I tried,” Jed said, holding out his hands. “Doc, I tried, but my legs…”

I didn’t wait for the rest. I tied the rope around my chest, handed the other end to Jed, and stepped out onto the ice. It groaned beneath me, threatening to give way. The cold bit through my boots, through my bones.

When I reached Sam, he was shivering so hard his teeth rattled. His nails scrabbled against my arm as I hooked an elbow under his chest. For a moment, the water pulled at us both, heavy and relentless. I kicked hard, felt the ice shift beneath me, and somehow we were both on the crust again.

Jed hauled us in, knees hitting the frozen mud. Sam was limp, but breathing. I wrapped him in my coat, hands numb, heart pounding.

Jed just kept saying, “Don’t let him go like that. Don’t let him go like that.”

III.

Back at the clinic, I got the heat lamps on Sam, rubbed life back into those stiff limbs, watched the steam rise off his fur. Jed sat in the corner, wet boots dripping on the tile, silent except for his breathing.

After an hour, Sam lifted his head. Looked straight at Jed. Thumped his tail once.

I swear the old man aged backward in that moment.

Sam made it through that night. And the next. Three weeks later, he was back to his slow patrols of the property, hips stiff but eyes bright. Jed brought me a bottle of cheap bourbon and said, “Not for the dog. For me.”

We sat on the porch and had a glass each, watching the sun set behind the cattails. The pond was frozen over again, but the air was softer, the promise of spring somewhere in the distance.

IV.

That spring, Sam’s hips gave out for good. It was a slow decline—one day he couldn’t make it up the porch steps, another he stopped chasing the mail truck. Jed called me to the house, voice quiet.

“Can we do it here, Doc? By the pond. He likes it here. Always has.”

I packed my kit and drove out. The grass was soft, the air full of birdsong. We spread a blanket in the grass. Sam lay down without being told, resting his head on Jed’s boot.

The sun was going down behind the cattails, turning the water gold. Jed kept one hand on Sam’s neck the whole time.

When it was over, Jed stayed like that for a while, hand gentle on the fur. Then he said, “Thank you for not letting him go in the cold.”

I didn’t realize how much that stuck with me until years later, when a young vet I was mentoring asked why I sometimes go out of my way—even when I know the odds are bad.

Because sometimes it’s not about winning. It’s about how they go.

V.

I still drive past Miller’s Pond sometimes. The cattails are taller than they were then. Jed’s gone now—buried next to his wife in the churchyard. But I can still see him standing in that winter wind, boots filling with icy water, begging someone not to let his dog die alone.

There are moments in this job you carry like stones in your pocket. Heavy, but worn smooth from turning them over in your mind again and again. This was one of mine.

I’ve been a vet long enough to know I can’t save them all. But I can damn well make sure none of them go thinking they were forgotten.

And maybe—if I’m lucky—someone will do the same for me.

VI.

Years passed. The town grew, the old faces faded. New families moved in, new dogs barked at the mail truck, new stories began. But some memories linger, echoing in the quiet spaces between appointments and long drives home.

Sometimes, on a winter evening when the wind is sharp and the world is blue, I’ll find myself thinking of Jed and Sam. I’ll remember the cold bite of that pond, the look in Sam’s eyes, the way Jed’s voice cracked with fear and hope.

I’ll remember the porch, the bourbon, the slow sunset. I’ll remember the way Sam lay down on the blanket, trusting us to do right by him. And I’ll remember Jed’s words: “Thank you for not letting him go in the cold.”

Those words became a kind of oath for me. In every difficult case, every late-night call, every moment when the odds were stacked against us, I’d hear them echoing in my mind. Not just for the animals, but for the people who loved them. For the old men in flannel, the kids with trembling hands, the families who needed someone to say, “I’ll stay. I won’t let them go alone.”

VII.

When I told the story to the young vet, she listened quietly, eyes wide. She was new to the work, still learning how to hold grief and hope in the same breath. She asked me, “Does it ever get easier?”

I thought about it. About all the dogs and cats and horses and birds I’d held in my arms. About the ones we saved and the ones we couldn’t. About the weight of those stones in my pocket.

“No,” I said. “But you get stronger. And you learn that what matters isn’t just how long they live, but how well you love them while they’re here.”

She nodded, tears shining in her eyes. I gave her a smile, the kind that’s half apology, half encouragement.

“It’s a good job,” I said. “Hard, but good.”

She smiled back, and I saw something in her—a spark, a promise. Maybe she’d carry her own stones someday, turn them smooth with memory and care.

VIII.

I still keep a picture of Sam in my office, tucked between files. Jed gave it to me the spring after Sam was gone. In the photo, Sam is sitting by the pond, sunlight on his fur, eyes bright and full of life. Jed’s hand rests on his neck, gentle and steady.

Sometimes, when the day is long and the losses heavy, I’ll take out that photo and remember. I’ll remember the pond breathing smoke, the cold that bit like teeth, the rope around my chest, the way Sam’s tail thumped when he saw Jed.

I’ll remember that sometimes, it’s not about winning. It’s about how they go.

And I’ll hope, when my own time comes, someone will remember to keep me warm, to hold my hand, to let me know I wasn’t forgotten.

News

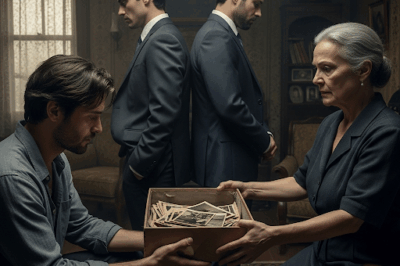

EL DÍA QUE MAMÁ REPARTIÓ LA HERENCIA, A MÍ ME TOCÓ UNA CAJA DE FOTOS VIEJAS Y UNA DEUDA”‼️

EL DÍA QUE MAMÁ REPARTIÓ LA HERENCIA, A MÍ ME TOCÓ UNA CAJA DE FOTOS VIEJAS Y UNA DEUDA” El…

En el corazón de la sierra, rodeado de campos de trigo y de encinas centenarias, se hallaba el pequeño pueblo de San Alejo. Era un lugar donde el tiempo parecía deslizarse más despacio, donde las campanas de la iglesia marcaban el ritmo de los días y las noches, y donde todos se conocían y compartían alegrías y penas como una sola familia.

La última promesa I. El pueblo y la promesa En el corazón de la sierra, rodeado de campos de trigo…

Después del funeral de mi esposo, mi hijo dijo: “Bájate”, pero él no tenía idea de lo que ya había hecho

Después del funeral de mi esposo, mi hijo dijo: “Bájate”, pero él no tenía idea de lo que ya había…

Esteban caminaba por el polvoriento sendero rural que conducía a su casa. El sol se despedía tras las colinas, tiñendo el cielo de naranja y púrpura. Sus botas, gastadas por el trabajo y los sueños, levantaban pequeños remolinos de polvo a cada paso.

La billetera de los deseos I. El sendero y la moneda Esteban caminaba por el polvoriento sendero rural que conducía…

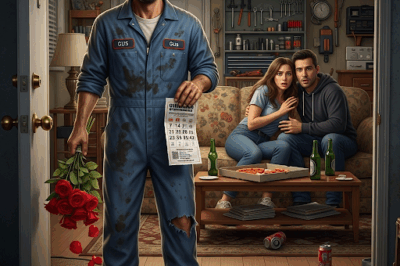

Le llamaban el boleto de los sueños, pero yo nunca creí en milagros. La vida me había enseñado que lo único que caía del cielo era la lluvia, y hasta esa llegaba sucia en mi barrio. Yo era mecánico.

El boleto de los sueños I. El taller y los sueños Le llamaban el boleto de los sueños, pero yo…

The rain had just stopped when Marcus Bennett spotted a silver Porsche Cayman pulled over on the side of the rural highway.

When the Rain Stopped The rain had just stopped when Marcus Bennett spotted a silver Porsche Cayman pulled over on…

End of content

No more pages to load